Robert Cloud was born on May 4, 1844, in Marshall County, Mississippi. At the age of sixteen, Cloud...

Railroads around the Shoals to Tuscumbia Landing

During the 1820s, increasing numbers of steamboats were beginning to arrive from New Orleans. Businesses and the merchants in Tuscumbia, Alabama knew that developing a steamboat landing at the bottom of the Muscle Shoals was of utmost importance to the economic success of the city. The most suitable location for this landing was determined to be on the eastern side of the mouth of Spring Creek as it entered into the Tennessee River.

Tuscumbia merchants took advantage of the flourishing steamboat trade and built large warehouses and loading facilities. However, the city of Tuscumbia was two miles away from the landing and warehouses. In order to solve the transportation problems between the two locations, resourceful citizens of Tuscumbia and the surrounding areas wound up constructing what would be the first railroad built West of the Appalachian Mountains.

The first railroad in the United States was started in 1828. Upon hearing of this new “mechanical device,” Courtland businessman David Hubbard traveled north to see how the railroad actually worked. Hubbard had heard of an innovative system for hauling coal in Pennsylvania and made the long, arduous trip to observe its operation. He wanted to know if this experimental invention might be adapted to haul cotton around the shoals. Hubbard found that the railroad proved to be of great advantage in hauling freight. One horse walking down a graveled path alongside the track could pull a car containing 40 bales of cotton. Hubbard returned home determined to launch a railroad project in Alabama.

The United States was just entering the period of railroad building, the advantages and disadvantages of which were being loudly debated in the legislative halls across the country. Tuscumbia was rising to a place of promise as a commercial emporium while enterprising planters of the Tennessee Valley were concerned over a means of overcoming the obstruction of transportation due to shoals in the river. As a result, the Alabama Legislature acted on January 16, 1830, to incorporate the Tuscumbia Railway Company with power to construct a railroad from Tuscumbia to Tuscumbia Landing on the Tennessee River that stretched just over two miles long.

Construction work on the new railroad project began on June 5, 1830, and was completed in two years at a total cost of $9,500. The iron for the 2.1 mile track was sourced from Russell Valley Iron Works; the first iron foundry in Alabama, as well as from the Napier Iron works in Tennessee. Workers also constructed Alabama’s first railroad depot. The depot was a charming three-story structure that measured seventy-five feet long and sixty feet wide. It was built on a hillside that overlooked the Tennessee River at Tuscumbia Landing. The building was erected at a cost of $7,000. The first of its three stories was built of strong rubble masonry, while the other two were built out of brick. The upper floor was level with the railroad and utilized an inclined plane that worked via horse power. The plane elevated freight from a floating wharf in the river through the depot to the railroad on the bluff above.

The quick construction and successful start to Tuscumbia Railway energized cotton planters and farmers in the area to build a railroad that could connect Tuscumbia with Decatur. The stretch of river between Decatur and Tuscumbia was only navigable during high water, and as such, the profit made off the local planters’ 87,000 bales of cotton annually still depended on the whims of the river. The result of this was the organization of the Tuscumbia, Courtland, and Decatur Railroad Company. A corporation designated in the charter granted on January 13, 1832.

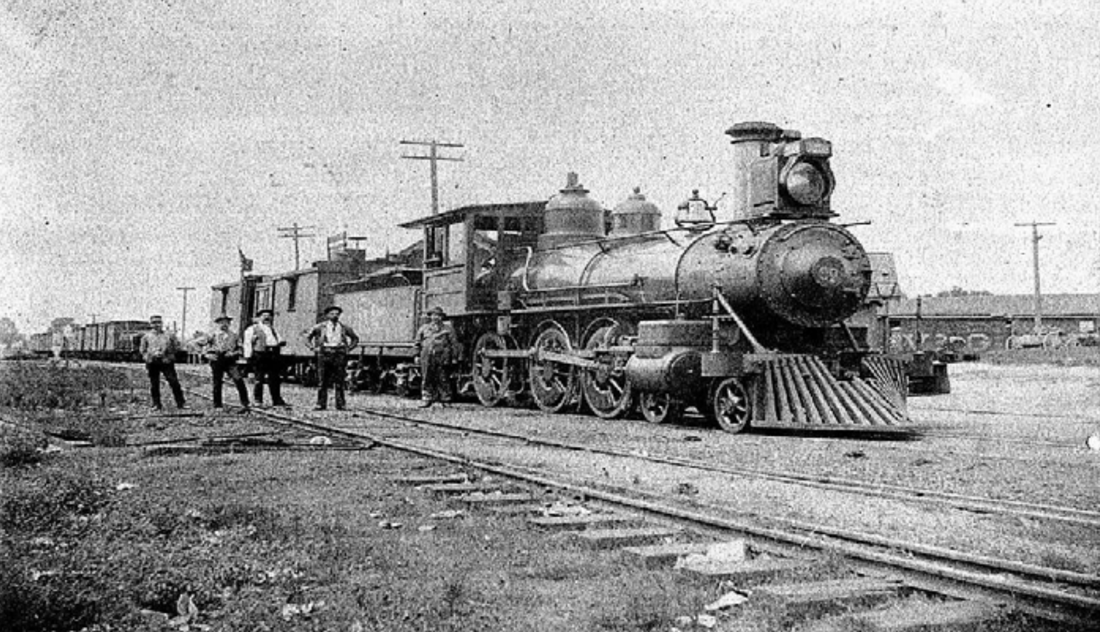

The first section of this railroad connected Tuscumbia to Leighton and was completed in August 20, 1833. The remaining section to Decatur was completed by December 1834. The construction cost of this nearly 45-mile stretch of railroad was $4,067.70 per mile. The tracks consisted of wooden stringers about five inches square laid down upon cross ties of red cedar and thin bar iron about three inches wide laid on and spiked to the stringer. In the middle of the tracks was the graveled horse path. Mules or horses constituted the motive power during the first few years of its operation.

The investors in the Tuscumbia, Courtland, and Decatur Railroad expected that steamboats would bring freight up river to the depot at Tuscumbia Landing, where it would then be placed on railroad cars and sent on to Decatur. There it would be placed on another steamboat and sent further on up river. The investors in the railroad were, in effect, gambling that the canal being created for easy navigation around the shallow Muscle Shoals would fail and that their new method of transportation would succeed. They were also well aware that the cotton planters needed a dependable way to get bales of cotton to a riverboat landing for shipping to New Orleans.

The horse-powered method of locomotion used in Tuscumbia was only temporary. In the early days of construction David Hubbard went to Baltimore to purchase engines; the company ordered three engines from the Stephenson Shops in England. The “Fulton” was the name to the first of these locomotives built for the Tuscumbia, Courtland, and Decatur Railroad Company. The Fulton traveled through New Orleans up the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the Tennessee Rivers to reach Tuscumbia Landing. The Fulton began its inaugural trip across the tracks on December 1834.

David Deshler was perhaps the most important figure surrounding the building of a railroad in Tuscumbia that circumvented the shoals of the Tennessee River. In 1830, Deshler was on the Board of Directors for the Tuscumbia Railway Company, and beginning in 1832, he would devote 15 years to building and supporting the Tuscumbia, Courtland, and Decatur Railroad.

David Deshler, and the Tuscumbia, Courtland, and Decatur Railroad made significant contributions to railway science and instituted a number of railroad “firsts.” Among these was a fundamental improvement in locomotive design. In 1836, Deshler came up with an innovative proposal for improving the standard four-wheeled engines. He suggested “putting her on eight wheels, carrying the front part on four small wheels, and using four adhesion or driving wheels, by means of outside cranks and connections.” This original idea from David Deshler would ultimately be adopted by railroads throughout the world.

Another Deshler innovation was the sand dome. Described by Deshler himself as

“an apparatus attached by means of which part of the weight of the tender is brought to bear on the driving wheels. A plan to obviate the want of adhesion is being worked out and a simple apparatus will likely remove this difficulty. My plan is to let a sort of hopper be arranged just forward of the driving wheels and above the frame of the engine from which a tube will be projected downward to within a small distance of the rail. The hopper will feed dry sand through the tube; a cock will control the stream of sand. Water may be used to the same advantage.”

The sand dome became another standard feature of future locomotives.

By the mid 1840s, the financial condition of the Tuscumbia, Courtland, and Decatur Railroad was seriously troubled. On September 22, 1847, the United States District Court foreclosed on a mortgage executed by the Tuscumbia, Courtland, and Decatur Railroad. The railway was sold off by the United States Marshall and purchased by David Deshler. On February 10, 1848, Deshler and his associates incorporated the Tennessee Valley Railroad Company by an act of the Alabama State Legislature.

After Deshler sold off his purchase to the newly incorporated Tennessee Valley Railroad Company, the company operated for several years until the railroad was again sold to the Memphis & Charleston Railroad Company. On May 1, 1857, water from the Mississippi River was carried by train to Charleston, South Carolina, and pumped into the Atlantic Ocean and ocean water was carried back to the Mississippi River. The Mississippi River and the Atlantic Ocean were at last connected by rail and by this symbolic exchange of water.

Bibliography

Cline, Wayne. Alabama Railroads. University of Alabama Press. 1997.

Johnson, Kenneth. "Tuscumbia, an early Railroad Center." The Journal Of Muscle Shoals History Vol. 17. Tennessee Valley Historical Society. 2002.

Johnson, Kenneth. "Tuscumbia important to railroad travel." The Journal Of Muscle Shoals History Vol. 17. Tennessee Valley Historical Society. 2002.

King, Gail. Historic Document Research, Geophysical Survey, Mapping, and Archaeological Inventory at Tuscumbia Landing, A Trail of Tears National Historic Trail site in Colbert County, Alabama. Southeastern Anthropological Institute. 2011.

Leftwich, Nina. Two Hundred Years At Muscle Shoals: Being An Authentic History of Colbert County 1700-1900 With Special Emphasis on the Stirring Events of the Early Times. The American Legion. 1935.